Stylish Stylolites— When Limestone Dresses Up Like Someone Else

Stylolites are some of Michigan’s toughest tricksters. Ask a group of geologists about stylolites and 9 out of 10 won’t know what you’re talking about. The topic is obscure, so why talk about them? Because Michigan actually has quite a lot of them and they can be confusing as heck if you’re unfamiliar.

What are they?

Stylolite, like many words in geology, comes from the Greek and if you were to speak Greek (which I’m betting you do not), this would all be obvious and we wouldn’t need an article. Stylos means pillar and lithos means rock and so a stylolite is a pillared rock. Now, these pillars are very small- it’s really more like serrations or tiny tiny columns running through the rock. And there’s lots of different kinds and they can have many different shapes, but we really don’t care about most of those in Michigan. Our stylolites are called horizontal stylolites and they occur in limestone.

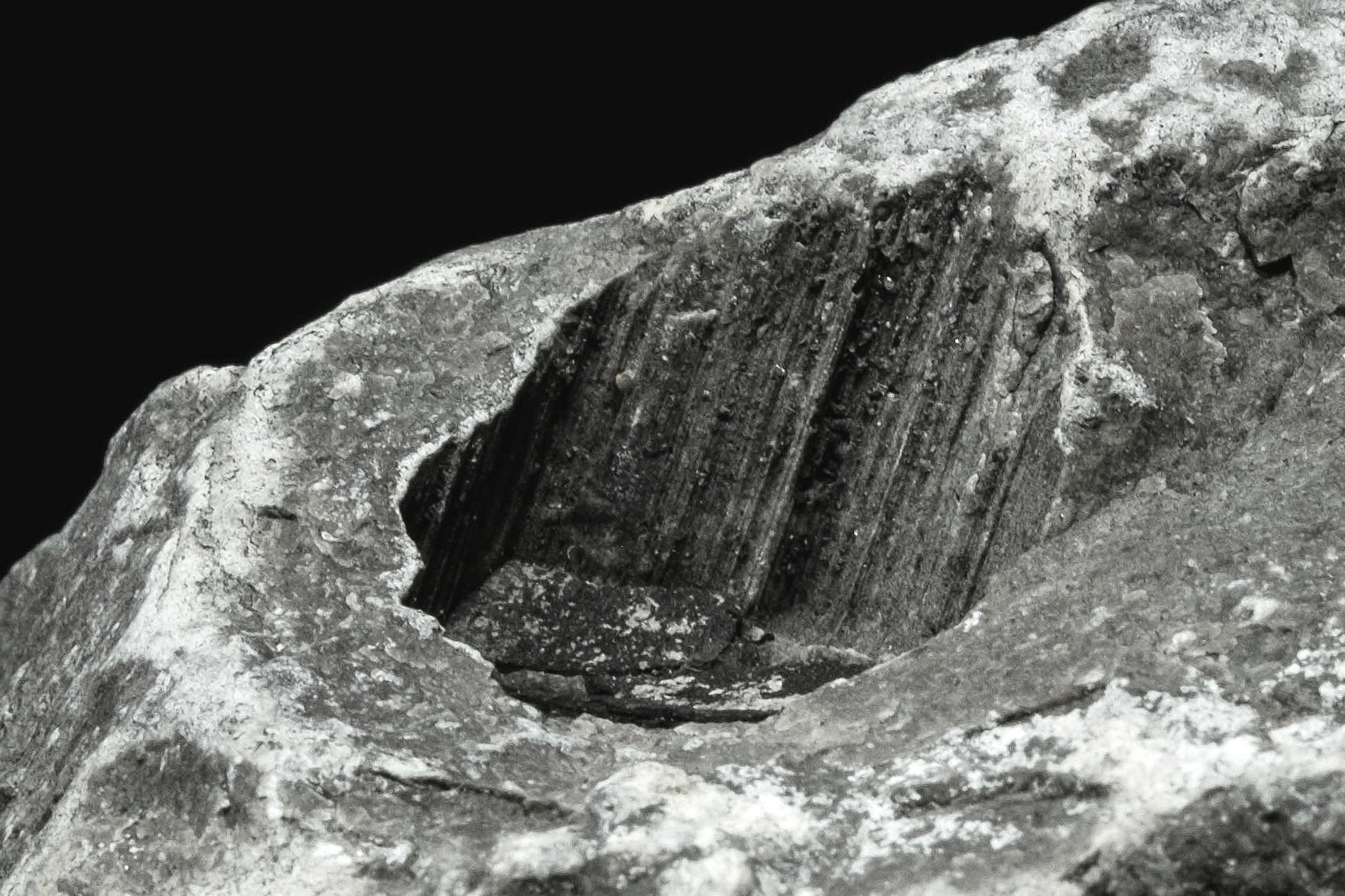

Stylolites forming on a specimen of limestone from Rockport, Alpena. Photo by Craig McClarren

Because there are many kinds of stylolites, doing your own google research on them can be very confusing: you’ll find reputable sources claiming they form sawtooth or sharks tooth wavy patterns and such… well, yeah, they do that in large boulders and in the ground, but in smaller rocks they won’t look that way. Ours tend to be very horizontal with tiny column structures, striations or whatever you’d like to call them, running vertically through them. Many people see these structures and believe they’ve found petrified wood. This has nothing to do with wood, however- these are weird structures within the limestone which formed in the shallow ocean.

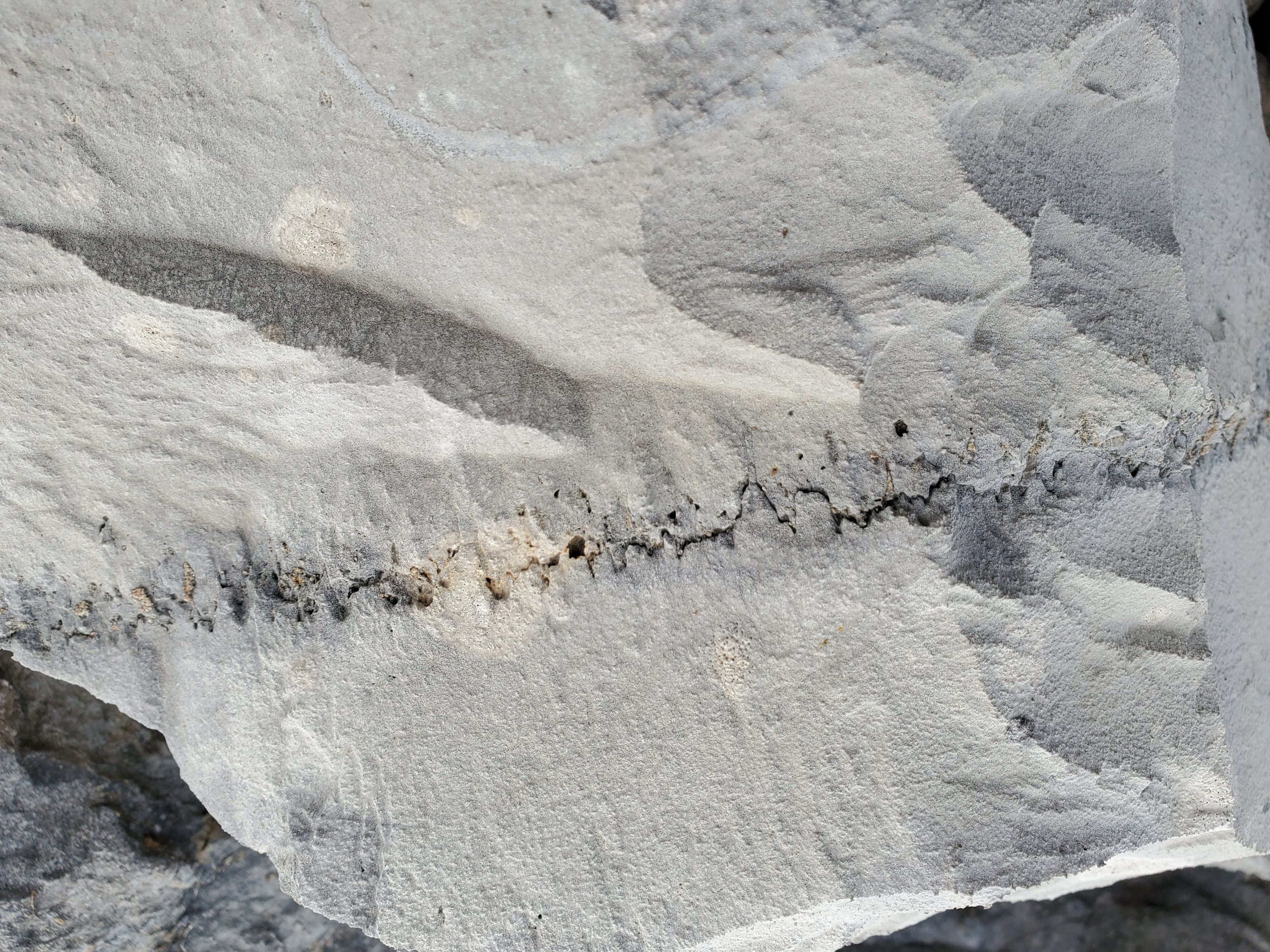

Shark tooth or sawtooth patterning in a stylolite on a limestone boulder, width of image approximately 1 foot at Rockport Quarry. Photo by Craig McClarren

How do they form?

Our stylolites form when the limestone begins to dissolve. Remember that limestone dissolves quite easily in even slightly acidic water. Every major cave in the world forms in limestone, as do sink holes. When water gradually makes its way through limestone, it can travel horizontally along bedding planes in the rock. As it dissolves its way downward through pressurized rocks, very slowly, it leaves empty spaces behind- think of them as micro-caves. Those columns or striations are the micro-cave versions of bigger cave features like columns and stalagtites and stalagmites: stylolites.

There was once some debate over how they form, but it’s quite clear now that this is how it works. If you’re lucky, you can find a stylolite that cuts across a fossil. The fossil above the stylolite will be perfectly preserved, but anything below is completely dissolved.

Where can I find them?

They form in limestone, which almost entirely covers the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and nearly half of the Upper Peninsula. And there has to be water… another thing our state tends to have in abundance. Stylolites don’t tend to be very hardy structures, though. Consider that they form when pressurized limestone dissolves, so they really don’t last long on a shoreline or in gravel where water is working on them all the time. Your best odds for finding stylolites is at a limestone quarry. Rockport, a publically accessible abandoned limestone quarry turned state park, has abundant stylolites. And remember the connection between dissolving limestone and caves and sink holes? Well, Rockport also has about a dozen sink holes you can visit if you’re willing to do a little hiking.

So keep an eye out for these trickster stylolites; they’re going to try to convince you they’re petrified wood or something else that doesn’t belong in Michigan. Don’t fall for it! Now you’re onto their game and you can call them what they really are: stylolites in limestone!

Three dimensional stylolites forming within a chunk of limestone. Photo by Cody Wiedenbein